->printable

(pdf) version

The following piece -- 'From

the "Primitive Droop" to the "Civilised Thrust":

Towards a Politics of Body Modification' -- was originally written

for the Body Modifications

Conference at Macquarie University in April 2003, and also became

part of my PhD thesis --The Body

as Fiction / Fiction as a Way of Thinking -- submitted

for the University of Ballarat in 2006 (see side panel). It is another

example of using material and characters from my novel-in-progress --

A Short (Personal) History of the Bra and its Contents

-- to create a text for presentation within an academic context

on a particular issue.

In this piece I

have montaged an essay-style narrative with distilled fragments from

the novel as well as pieces written specifically for this work to create

a new hybrid (cross-genre or fictocriticism) text.

I found that having

set up the novel as a laboratory, I was then able to use the different

characters and their interests and experiences to actively explore some

very knotty issues regarding the discourse around body modification.

And I was able to do this from an unusual perspective precisely because

the novel brought together such a diverse range of topics - from issues

to do with identity and subjectivity, gender, the corporatisation of

medicine, the implants controversy, the way breast-feeding (and pregnancy)

confounds the notion of an individual citizen-body with inalienable

rights, through to fashion history and an intense exploration of the

seemingly superficial and benign (some would even say healthy) body

modification practice of bra-wearing.

Writers on body modification often find themselves in an impasse, where

their post-structuralist critique of the notion of a 'natural' body

then seems to render them powerless to criticise any type of body modification

practice, even those types or trends which they may personally find

disturbing - for instance, some of the more serious forms of normalising

surgery available within contemporary western capitalist culture such

as breast augmentation. The general argument is along the lines of 'we

all modify our bodies, so none of us can criticise any other culture,

group or individuals' choices'.1

Through my characters,

and their different circumstances, I have tried here to carve a way

out of this ultimately universalising 'we all do it' narrative, and

start to hone in on some very specific historical circumstances. We

all might modify our bodies, but not all of us do it at the end of the

twentieth century, under capitalism, and within such a strong scientific,

philosophical and cultural legacy of the mind-body, culture-nature split...

____________________

Preamble

I want to look

at some of the difficulties in trying to develop an ethics or a politics

of body modifications at the cusp of the twentieth and the twenty-first

centuries, exploring this within the context of a novel I'm writing,

set in 1999, called A Short (Personal) History of the Bra and its Contents.

One of the reasons

I like to work with fiction is that it allows me to create a discursive

field -- an artificial space -- in which a whole range of issues and

ideas can co-exist and work off each other. Ideas, for instance, to

do with subjectivity, gender, sexuality, and the privatisation of bodies;

the implants controversy, the cancer industry, the corporatisation of

medicine and various current debates within science; fashion history;

and so on.

In this field,

ideas and facts and bits can rub shoulders -- and thus cross-fertilise

and react -- simply by virtue of an imaginative association, a linguistic

chain, an event sequence, or via the relationships that form between

a cast of characters.

During the years

I've been working on this novel -- which is still very much a work in

progress -- quite a large cast has grown up around the narrator, Angela,

and a few of these will be making a guest appearance here today.

For instance, apart

from Angela -- who works at the State library -- there is Natalie, her

bosom buddy, who, with Angela, is researching and collecting for a Dr

B, who is creating an underwear museum in a small country town. Then

there's her downstairs neighbour Gail, mother of three, with a new baby

born soon after the novel starts. Her next door neighbour Bob (short

for Roberta), a tattoo artist. Maddie, her favourite aunt, currently

using mainly alternative and non-toxic methods to deal with her breast

cancer. And Wanda, who has various connections to the others and is

also the artist in residence at the State Library, working with street

people in the basement, helping them workshop their costumes for the

party at the end of the millennium.

(Well, I never

said it was realism.)

--------------------------------------

A

few years ago journalist Virginia Postrel, writing in defence of breast

implants, declared:

'The Biological

Century is upon us...The body, not the Internet, is the next frontier.

We are extending control over life itself, over our lives ourselves.

That control will, undoubtedly, have some unintended consequences, and

bring some tragedies. That is in the nature of things, the nature of

life. But so is the attempt to better nature, to bring the born into

the realm of the made, to assert human ingenuity against chance. The

debate over breast implants is only incidentally about the venality

of lawyers or the benefits of a C cup. It is about who we are and who

we may become. It is about the future of what it means to be human.

' (2)

*

Gail wants to

know: When is it not ok to modify the body?

With every culture,

every individual engaged in body modification as a daily practice, is

it possible to draw a line?

And if so, how,

and where?

*

Natalie says:

Well it's like this: having to wear make-up is oppressive; being able

to wear make-up is creative and fun.(3)

But are choice

and compulsion so clear cut? (I'd imagine that a few of the women on

the Silicone Survivors email list, for instance, might be interested

in debating this one.)

*

Or perhaps you

could evoke the difference -- as Bob has been known to do -- between

body modifications that reinforce notions of 'normality' and pathologise

difference; compared to ones that aim to 'individualise', encouraging

variety and tolerance.

Except that 'individuality'

itself is such a loaded term. And a bit like beauty: many beholders.

As a teenager I

remember a minister raging against our incredible conformity -- pointing

out that all of us in the room were wearing blue jeans. Strutting around,

meanwhile, in his two-piece suit and tie.

Indeed, it could

be said that what is so effective about the normalising and regulatory

practices of post-modern culture is this very ability to produce individuals

in such a variety of ways. (4) With Bob's tattooing no more outside

of the contemporary power nexus than a thousand dollar suit, or a nose

job.

*

One morning, I'm

in the shower and I overhear Bob and Gail out in the courtyard. Dora,

the receptionist for the plastic surgeon who owns the building, has

just been to collect the rent.

Bob says, 'Look,

I'm not saying there aren't some risks with piercing, too. There's the

risk of infection if you don't look after it properly. There is the

possibility of a mistake and nerve damage. But I've never seen anything

serious in that way (not like with implants). And an infection from

a piercing is only temporary -- if it gets real bad you just remove

it.'

Gail says, 'So

permanent modifications, is that the problem? But tattoos are permanent.'

Bob says, 'There

are a lot of ways you can look at body modifications.(5) You could divide

them into temporary compared to permanent. But it's not really so clear

cut. I mean, you can take a pair of shoes off, but if you're wearing

them every day from childhood, your feet are going to be permanently

altered.'

Gail says, 'Yeah,

but they would be altered if you didn't wear shoes, and walked on rocks

and ground for years. I mean, they're going to be altered whatever you

do, just by growing older…'

'Ok…' Bob

says. I rub shaving foam on my legs while she chews this one over, listening

to the clip of her shears as she moves around the courtyard checking

on her plants. 'Ok, well yes,' She says finally. 'Life is a body modification

process... But if we're talking deliberate modifications, another way

it's often talked about is the difference between soft-tissue and deep-tissue

modifications, or invasive compared to non-invasive; say ones that involve

cutting into the body compared to those that don't. But by that definition,

where do you put something like Burmese neck rings? No cutting there,

just gradual manipulation… but I think they'd be considered severe

modifications by anyone's standards...'

I nick my leg slightly

with the razor, and a little trickle of blood runs down in amongst the

foam.

'So then, you have

the adornment, manipulation, mutilation argument. Adornment,' she says,

'can just be a surface thing; or it can involve manipulation of body

tissue; and over time manipulation can involve mutilation… '

Gail says, 'So

the litmus test is does it mutilate, and anything that mutilates is

bad.'

'Well I don't know

if it's always 'bad'', says Bob, 'but it is serious.. the most serious

thing you can do, and it needs to have the most careful consideration

and a lot of discussion around it. There has to be a good reason for

it -- for instance, cancer. Or to prevent conception. Or if you want

to change your gender markers because you feel suicidal as you are.

Or lip plugs, for instance: some say they began as a protection from

evil spirits and then increased in size when it was discovered that

slavers couldn't use those with lip plugs. And then it continued because

it became such a part of their community identity and history of survival.

That's why you can't say any modification is bad per se, it has to be

in the context of things… It has to be constantly questioned and

challenged.'

'So: shoes don't

mutilate, so they're ok?'

'They can mutilate

if you wear high heels a lot and throw out your back. They also deform

your ability to walk over rocks, whereas no-shoes only deforms your

ability to wear shoes.'

I use a pumice

stone on one of my corns.

'Now, I like this

argument,' says Bob, 'because by this definition tattoos and most piercings

are simply adornment: at the lower end of the scale. Whereas wearing

a bra, for instance, is a serious body modification.'

Gail says, 'Oh

come on Bob, not this again.'

'It's true,' Bob

says, 'Bras can mutilate the functioning of an important body system

-- the lymphs. And while most parents go ballistic if their kids get

a tattoo or a tongue piercing, they happily strap their teenage girls

up into a bra the minute they begin to sprout. Barbaric really.'

*

Barbaric to some,

liberating to others.

Back in 1970, my

first day of secondary school, there was a girl called Christine Hill,

who looked a little bit like Christine Keeler (long tawny hair, white

fine-featured face). She claimed her school uniform hadn't arrived,

so instead of the regulation blue check dress she wore a yellow chiffon

blouse with ruffles at the cuffs and throat.

A see-through blouse.

And under the see-through

blouse, as clear as day, the white straps and delicate heart-stopping

lines of a bra.

The teachers swooped

and she was covered up with a borrowed jumper. But it was too late.

The serpent had entered the garden. We had glimpsed the perfect apples,

and knew ourselves to be naked.

*

Down in the basement

of the library, Wanda is giving a lecture. She writes a quote from Elizabeth

Wilson on the board. 'Clothes,' she says, pointing to it, 'are the poster

for one's act.' (6)

The workshoppers

huddle over their styrofoam cups of coffee, pulling an assortment of

many-layered jumpers and coats and cardigans around them.

'When we wear a

bra, for instance,' Wanda says, 'we perform not just gender, but also

western post-colonial ideals of progress and control over nature.'

A woman in the

front row scratches her breasts and then jiggles them up and down, getting

a laugh from the others.

'Every piece of

clothing, every act we do with or upon or allow to be done to our bodies

is a part of a constant articulation and rearticulation of power relations

in all their complexity.'

She switches on

the overhead projector. 'Take for instance,' tapping the images on the

screen, 'some of the things repeatedly used to designate feminine helplessness

and frailty -- high heels, tight-lacing, wigs, false eyelashes, push-up

bras. You have to be tough (and determined) to wear them and survive.

'You become weak,

or powerful. Or both.'

*

What does the bra

enable?

What does it restrain?

*

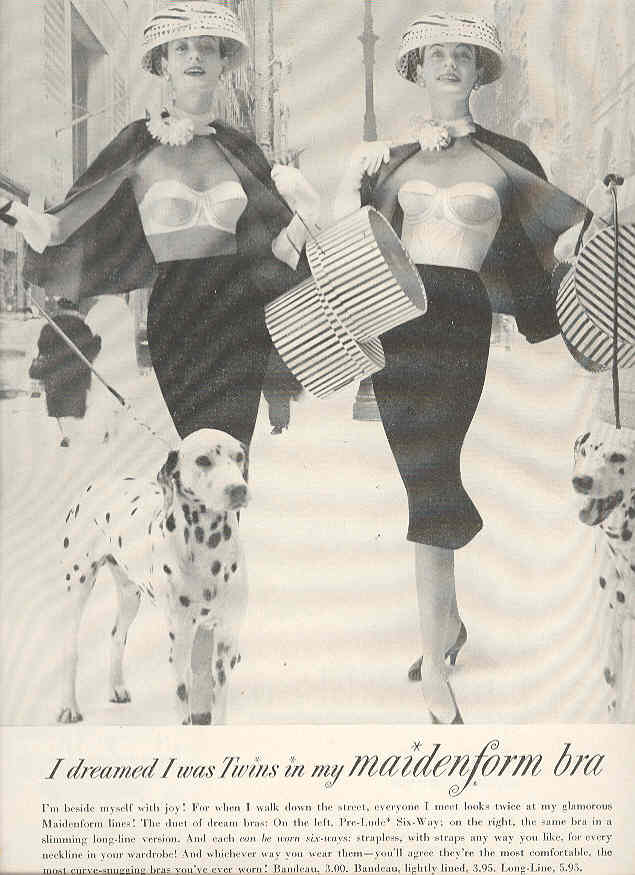

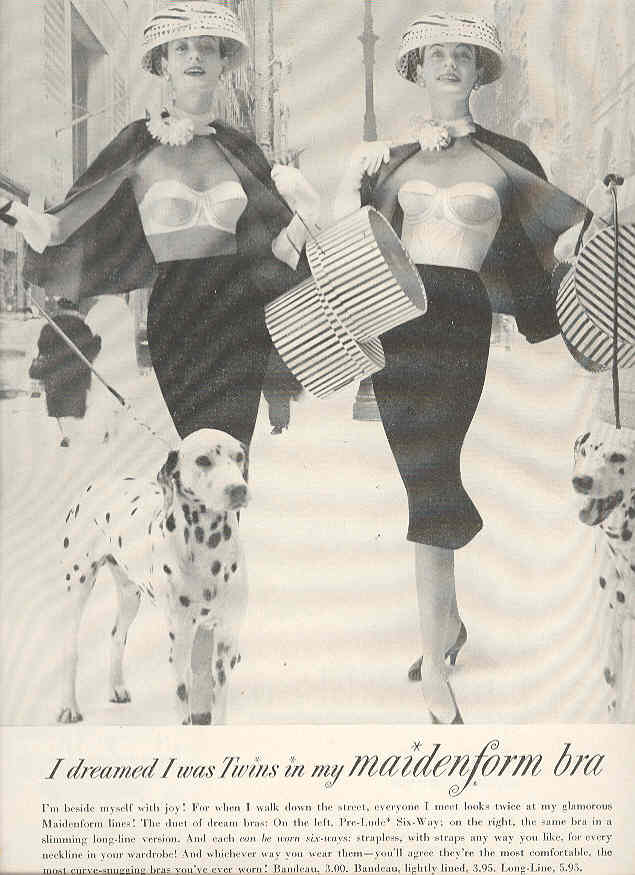

Natalie says: 'The

bra is the ultimate symbol of modernity: progress; comfort and the avoidance

of pain; perfection.'

Gail says: 'Classification,

competition, assessment.' (7)

Natalie writes

a card for Dr B, quoting the words of Anthony Forge, Professor of Anthropology

in the 1960s at the London School of Economics, about the bras achievement

in 'converting the primitive droop into the civilised thrust.' (8)

Bob says, 'The

civilised thrust doesn't eradicate or diminish pain, Natalie.' She is

speaking from experience -- a long history of fibrocystic breasts before

she threw away her bra. 'It creates whole new types of pain, and then

spreads it around differently. Relocates it somewhere else.'

She says: 'I mean, really, it's insane that so many women these days

feel uncomfortable unless they're wearing this thing that leaves red

welts and grooves on their bodies, damages delicate tissue, atrophies

muscles and ligaments, often causes chronic back ache or debilitating

breast pain and lumps, and by cutting off the normal lymphatic flow

and allowing toxins to concentrate in breast tissue may well be a key

factor in high breast cancer rates.' (9)

*

But as Bob herself

said, there are no absolutes.

At work I write

out a card for Dr B:

The World's Smallest

Waisted Woman was Ethel Granger: who trained herself gradually over

a period of eight years to wear a corset that reduced her waist to a

tiny thirteen inches, basically just enough room for her spinal column.

By the time she died in 1974 all her internal organs had been displaced,

for even without the corset her waist by then measured only 16-17 inches.

Yet she lived a full and healthy life into her eighties, outliving her

husband, Will, and for many years riding a small motorbike to her work

each day in a London corset shop. (10)

*

Actually Bob rather

approves of Ethel Granger. Serious modifications, she says, require

a serious attitude. Yet is it amazing how even major surgery can be

undertaken lightly if it is described as being for 'cosmetic reasons'

(advertised alongside lipstick and face creams).

On life and tattoos,

Bob says: If you truly want to be altered by it, you have to accept

the pain.

She doesn't approve

of body modifications that require anaesthetic -- not because of the

cutting thing, but because, she says, your conscious and unconscious

fears and feelings, especially any feelings of shame, are simply drugged.

She says, often they will surface later and affect your experience of

the modification, and your healing.

*

Tony, the video-shop

guy, slaps a copy of The Graduate on the counter for us and says: 'I'll

give you a one word piece of advice about the future: plastics.'

Gail says, 'What?'

Tony says: 'The

Graduate. One of the men at his father's cocktail party says it to Dustin

Hoffman...Well, actually, he does, but I read it on a Pamela Anderson

website.'

*

In pure technological

terms, with the combinations and permutations of surgery techniques,

mass media effects, globalisation, and genetic engineering, for instance,

the ability to alter our bodies has increased exponentially.

Fuelled by capitalism

and the corporatisation of medicine, an array of possibilities are offered

alongside an intensely modern, privatised notion of the body.

Western bodies

-- no longer owned as slaves or serfs -- are sold as a kind of personal

capital, to be invested in, maintained, worked and improved. With the

success of equality feminism, even women's bodies have nominally been

extended the masculine unequivocal and exclusive owner-occupier rights:

rights to derive pleasure and value from one's body, rights to change

it -- with only the lingering abortion debates and the occasional storm

over breast-feeding left to challenge this. (11)

*

As Cher told People

magazine in 1992: 'You know if I want to put tits on my back, they're

mine.'

*

The risk, of course,

as many critics of genetic engineering have pointed out, is a kind of

consumer eugenics.

Even apart from

this, it is ironic how all our manipulation and modification and adornment

of bodies in the name of individualism, greater pleasure, aesthetic

delight, choice, personal freedom and power has led to such an epidemic

of body-loathing and despair .(12)

With the body seen

as an ongoing project and investment, the sense of incompleteness is

often overwhelming.

So we keep adding

to the body -- clothing, hair dye, accessories, shoes, jewellery, hairspray,

push up bras, implants, tattoos, piercings, more clothes, newer clothes,

less clothes, muscle building… And we keep taking away: dieting,

liposuction, depilation…

(Peering into the

fridge late at night: if only I can find the right thing to put into

my body. I just need..? Maybe this chocolate ice-cream, with some of

these biscuits… ?)

*

Not one of the

choices we make about our bodies, not one of the judgements we make

on our bodies, or the pleasures we derive from them occur in a vacuum.

They all occur in specific, complex and changing social contexts. Every

act we do contributes to changing these contexts. That's why every act

we do is important, and every act is social.

*

At a dinner party

a couple complain about the way they now(days) 'have to' fork out to

have their children's teeth fixed by an orthodontist. I remember the

husband's astonished reaction when I described it as a body modification,

and compared it to breast implants and nose jobs (all aiming at uniformity,

all correcting perceived deformities that are culturally determined

). (13)

After all, they

only 'have to' because 'everyone else is'. That is, everyone else in

the class they want their children to be at home in and to succeed within.

Without their teeth 'done', their children might stand out as working

class, or odd. Marked for life. (The sins of the parents...)

*

Nose jobs in Colombia,

eye surgery in Japan, footbinding in traditional China, the war of the

bustlines on The Bold and the Beautiful… A constant shifting of

the goal posts.

*

Gail says, 'It's

-- I don't know -- a spiritual ecology thing, or about cultural ecology:

about the diversity of our bodies as a resource.

'When people say,

well if I can make myself feel better by having implants or a tummy

tuck, then why shouldn't I? This to me is the same as saying well if

I feel more powerful having a big car rather than a small car, why shouldn't

I have it? Or, if I can afford a boat that uses a year's worth of petrol

for a half hour pleasure ride -- hell, why shouldn't I just go ahead

and get that boat?

'Every person on

television who has a face lift to keep their job makes it harder for

those who don't. We are all so inter-connected. Together we make up

an aesthetic environment…

And we either value

difference and variation, or we don't. And I'm not saying no one should

make changes, but that it's complicated. And that when we make changes,

just like when we decide which car to buy, or which soap powder to use,

we should at least be thoughtful about it. As individuals, and as a

community.'

*

'Well I always

like to keep a few spots of virgin forest on my body,' Natalie says,

'like my pubes.' She glares at her boyfriend, 'Even if this is a bit

too wild for some people's tastes.

*

At the end of the

20th and start of the 21st century, still operating from Newtonian physics

and the mind-body split, medical science keeps offering us the promise

of control over our bodies, just as biological science kept offering

for so much of last century its fantasy of control over nature. (14)

As if we were somehow above it, or outside of it, independent of it.

As if we (or our minds) are the knowing and intelligent ones, and nature

(or our bodies) merely a passive surface or material.

*

My aunt Maddie

says: your body is so much more than just a machine to get your mind

where it wants to go, it is an integral part of an immensely complex

mind-body-spirit system. A precious object of great power, an extraordinary

piece of technology on loan to you for both pleasure and learning.

She says, The body

works in partnership with your spirit, and its intelligence and ways

of knowing are as intricate and vital as those of the mind. It is your

responsibility to look after it, your privilege to learn from it.

She says the limits

of your body, it's illnesses and moods, are like white rocks defining

your path, so that you can see it even in the dark.

*

Of course Maddie

only says this on her good days, when she's feeling calm and balanced.

On the bad days -- the turbulent ones -- she too rails against her body,

just wants the cancer to be gone, to disappear, just wants to be 'normal.'

And then she rides

it out, and the calm returns, and she knows there is no normal.

*

Bob says she can

no longer imagine her body -- can't even mentally visualise it -- without

the tattoos and piercings.

She says the original

Christian objection to tattooing, apart from it being a symbol of base

sexuality, was that it disfigured that which was fashioned in God's

image. (15)

Which

means that by tattooing your body, you are seeing yourself not as something

formed in God's image, or by a God, but as a part of God. You are not

just inhabiting your body, but continually co-creating it.

*

'Yes,' says

Maddie. 'A co-creator; not a dictator.'

*

I have titled this

paper 'towards an ethics or politics of body modifications', because

I have no answers, just some questions I think it is worthwhile we continue

to ask.

Like: what functions

within a cultural system do particular body modification practices serve

at any particular time? What are their long term and social consequences?

And what kind of power relations do they reinforce, reproduce, foster

or create?

The technological

imperative is often conflated with a vague notion of an unstoppable

(and therefore natural and right) 'progress'. But progress is always

a relative term, meaningless and unmeasurable without some specific

defined goals.

In other words:

just what kind of a place is this that we're creating with our bodies?

*

For

the references and notes for 'Towards a Politics of Body Modifications'

see side right hand

panel ----------->

printable

(pdf) version of this essay

To

cite this essay:

Beth

Spencer. 'From

the "Primitive Droop" to the "Civilised Thrust":

Towards a Politics of Body Modification'. Paper presented at the

Body Modifications Conference, Macquarie University, NSW,

Australia, April 2003. <http://www.bethspencer.com/bodymodifications.html>

email: beth at bethspencer dot com